Contrary to the conceived wisdom, Republicans aren't

searching for the 21st century Ronald Reagan; they're looking for a modern day

Barry Goldwater. They don't want a president who, like Mr. Reagan, will bail

out banks; who, like Mr. Reagan, will raise taxes; or, who, like Mr. Reagan,

will leave office with a stronger national government and more federal

bureaucrats.

Practicality (and a healthy portion of context) be damned, Republicans

yearn for someone who will reaffirm Barry

Goldwater's famous conservative aphorism: "extremism in the

defense of liberty is no vice."

Such cravings explain the ongoing flirtation with Ron Paul,

who began his executive aspirations not as a Republican, but as a Libertarian

in 1988. Since, Mr. Paul has cemented his place as an influential member

of the right. He has written numerous books on libertarianism, effectively

founded the Tea Party, and become a strong contender against Mitt Romney, the de facto Republican nominee. Indeed, with his

near constant exhortations of "liberty" and "intellectual

revolution," Mr. Paul seems a prime candidate to follow in Mr. Goldwater's

ideological footsteps.

Yet voters have right to be wary; Mr. Goldwater was

demolished in the 1964 election, and things will only be more difficult for his

successor.

Unlike Mr. Goldwater, Mr. Paul must contend with the

religious right, which only entered the GOP during the Reagan Era, but now

represents a sizeable portion of Republicans. Mr. Paul also faces an

international threat more nebulous than the communists of the Cold War, which

makes a coherent foreign policy more difficult to find.

His most challenging obstacle, though, is this: Support for

libertarianism has a ceiling, and for good reason.

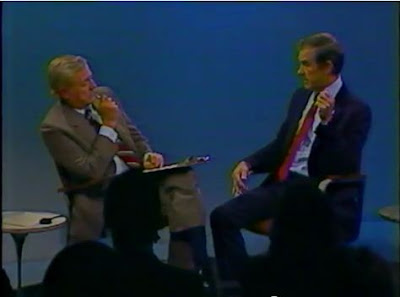

If intrigued, watch this 1988 episode

of Firing Line, in which William F. Buckley, Jr. — the harbinger of conservatism

and a good friend of Mr. Goldwater's — continually bested a younger Mr. Paul in

an hour-long discussion on libertarian philosophy.

|

| Ron Paul (right) with William F. Buckley, Jr (left) on a 1988 episode of Firing Line |

Said Mr. Buckley in that iconic voice: "As someone who

occasionally calls himself a libertarian, I regret the extent to which the

libertarian position is discredited by positions via a kind of reductionism

that is simply incompatible with social life."

Quite right. If Mr. Paul can be accused of anything, it's

reductionism. In but one sentence Mr. Buckley acknowledges what Mr. Paul (and

many of his supporters) fails to: Liberty is complicated.

It's easy, when waxing philosophic, to refer to liberty as

an ideal in which all can partake unmolested. But when determining the laws by

which a society must abide for its preservation, we find that liberty (in the singular) is in reality a

series of liberties (in

the plural), and that these liberties,

more often than not, rub against one another.

Consider the Hobbesian case, in which one's liberty to murder

is superseded by the other's right to life. Such an exchange is not only

uncontroversial, but beneficial.

Now up the ante. What happens when protestors display their

rights to speech and assembly, but in so doing, and by breaking no laws,

significantly disrupt surrounding business practices? Again, we have a conflict

of liberties.

And what of the 1964 Civil Rights Act (a particular sticking

point of libertarians everywhere, including Messrs. Paul

and Goldwater),

which rescinded individual property owners' right to serve whom they pleased,

and exchanged it with another, better right: that of any and all persons to

make use of public accommodations? Once more, we are engaged in a trading of

liberties.

This last example undergirds the truth (or complication)

that ultimately constructs libertarianism's ceiling of support: the status quo

inevitably offends the liberty of some, which, a posteriori, implies that a government

doing something can be as good, if not better, than a

government doing nothing. Subsequently, it falls upon us, as a democratic

republic, to decide which liberties are maxims, and which can be exchanged or

infringed upon for the betterment of society.

To parse these questions, we often employ John Stuart Mill's

thesis in On Liberty: "The only purpose for which power can

rightfully be exercised over any member of a civilized community, against

[one's] will, is to prevent harm to others."

(And like any good democratic republic, there is plenty

debate as to what constitutes "harm.")

But until libertarians like Mr. Paul realize how complex the

enterprise of liberty really is, he — and his son for that matter — has not the

faintest hope for the White House.

Those who enjoyed this editorial, might also enjoy: Presidential authority - Obama, Romney and bin Laden

Those who enjoyed this editorial, might also enjoy: Presidential authority - Obama, Romney and bin Laden

No comments:

Post a Comment